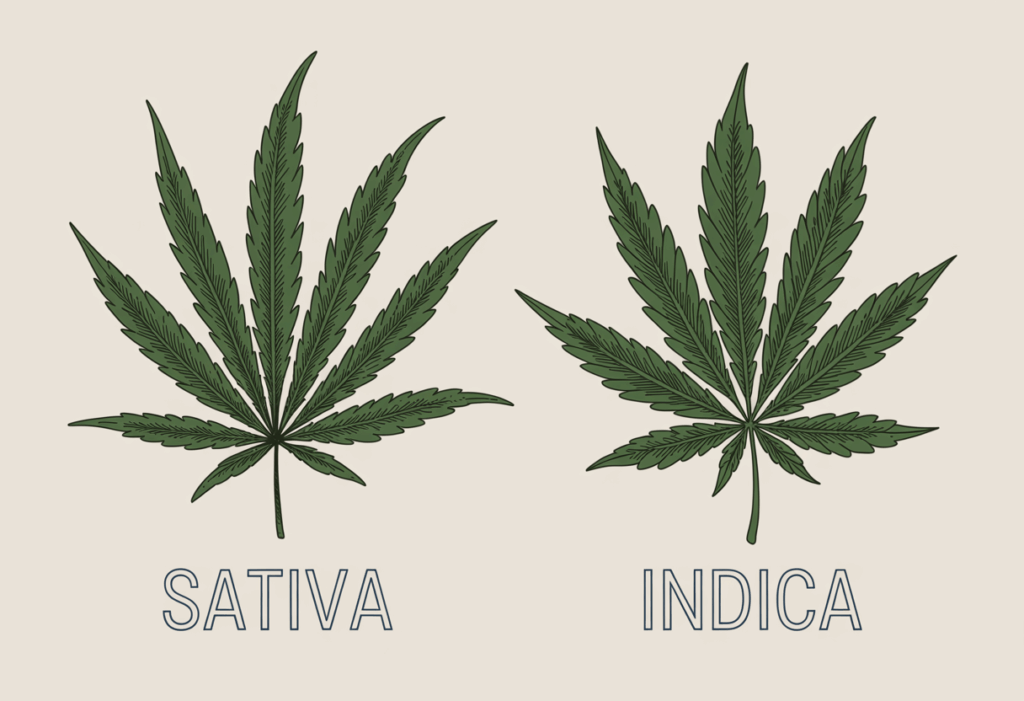

If you consume cannabis, you are more than likely aware of the categorization by which various strains are distinguished from one another. The terms sativa, indica and hybrid are descriptors that imply specific qualities, which can represent a deciding factor for discerning patients or customers hoping to find their ideal strain.

Strains of the sativa species are typically understood to produce heady effects, facilitating what enthusiasts describe as an uplifting, energizing high. Some proponents associate sativa consumption with an increase in productivity, creativity and focus.

Meanwhile, the indica species is commonly associated with decidedly more mellow vibes. Terms like “couch lock” and “body high” are often used in reference to the sedative properties attributed to strains labeled indica.

Hybrids, as the name suggests, are strains containing genetics from both indica and sativa plants. Individuals who prefer hybrids are usually looking for an agreeable balance between what are traditionally seen as the stimulating effects of sativa and the sedative results delivered by indica. While some prefer so-called 50/50 strains, comprised of equal parts indica and sativa, others seek varying ratios based on their desire for indica-heavy or sativa-dominant strains.

As is the case throughout the entirety of commerce, cannabis consumers are creatures of habit. As such, many are adamant about their preferences, often for the sake of sticking with what works.

But what if “what works” is more perception than actual science?

Recent years have seen an increasing availability of research and analysis surrounding the characterization of cannabis. The resulting data has been interesting, to say the least.

One such example can be found in a peer-reviewed 2015 study, which compared samples that carried identical names to each other, as well as to all other genotyped samples. Ultimately, 35% of the samples were found to be more genetically similar to samples with different names than those of the same names.

Researchers concluded that it was not possible to determine the genetic identity of a marijuana strain based on its name or genetic ancestry. This outcome effectively renders the indica/sativa metric flawed at best.

Given these findings, it’s clear that sedative characteristics are not intrinsically exclusive to indica strains, nor are invigorating effects solely inherent in sativa strains.

So, if everything we thought we knew about sativa and indica is wrong, what is the truth?

When it comes the distinct differences between one type of high and another, the objective fact remains that some weed strains wake you up while others put you to sleep.

However, contrary to previous assumption, the degree to which a particular strain produces one result or the other is entirely dependent upon the particular combination of that plant’s cannabinoids, terpenes and other compounds—none of which is specific to one species or the other.

This has been a hard truth to accept, it would seem, considering the intervening 7 years since the study was released have seen no apparent change in how strains and their effects are characterized. The indica/sativa binary seems to be one to which the industry remains intent on clinging.

If that is true, they may not like this next part.

Pure indica and pure sativa strains are increasingly rare in today’s cannabis market. In fact, it is possible that some of the goods labelled as such—and there are many among the dispensaries in Arizona—may be incorrect in assertions regarding purity.

This isn’t necessarily intentional. Many cultivators receive their seeds from large seedbank operations, many of which cannot, or otherwise do not, certify any official chemical composition for a particular strain or seed, making it difficult to confirm the veracity of a claim regarding a resulting plant’s pedigree.

Outside of occasional small-batch runs upon which one might fortuitously stumble, a lot of the weed that makes its way to market is hybridized to some degree.

Even legacy landrace strains, such as Durban Poison or Afghan Kush, have been through generations of cross- and inter-breeding, to the extent that products carrying these names are possibly descendants, rather than the original strain.

Of course, it’s not necessarily a bad thing that these heirloom strains have been altered. One of the things you often hear from smokers of the original landrace strains is the comparatively stronger weed that they encounter “nowadays.”

That significant increase in plant potency is often an effect of intentional breeding aimed at sequencing out undesired elements, some of which may have hindered the production of resin-laden trichomes that directly translate to THC potency.

The genetics of a majority of strains, species, phenotypes etc., have been comingling for some time, and it would be reasonable to assume that such fraternization might result in a diverse hybrid landscape, replete with the best qualities of many of those classic strains.

One thing is for sure, for such a vast and rich field of potent, flavorful strains, it seems almost disingenuous to insist on jamming them into one of two ill-fitting categories.

To continue to limit cannabis with such categorization would be, as psychopharmacologist Dr. Ethan Russo is quoted as saying, “total nonsense and an exercise in futility.”

In a published conversation with Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, he insists that because of the hybridized nature of cannabis today, the only way to truly determine how much of a desired effect a plant is likely to produce is to conduct a comprehensive full panel assay or analysis, which would determine how much of each compound is present in a product.

While full panel testing is available for marijuana in Arizona, it’s not required under existing ADHS guidelines. However, it’s always worth checking your product’s packaging to see if it has testing results, which are often accessible through a QR code if they aren’t listed on the label. Even if all you get is a basic listing of cannabinoids, it may serve you better than the indica or sativa distinctions.

***

GreenPharms is more than just a dispensary. We are a family-owned and operated company that cultivates, processes, and sells high-quality cannabis products in Arizona. Whether you are looking for medical or recreational marijuana, we have something for everyone. From flower, edibles, concentrates, and topicals, to accessories, apparel, and education, we offer a wide range of marijuana strains, products and services to suit your needs and preferences. Our friendly and knowledgeable staff are always ready to assist you and answer any questions you may have. Visit our dispensary in Mesa, or shop online and get your order delivered to your door. At GreenPharms, we are cultivating a different kind of care.

Follow us on social media